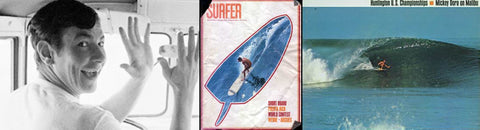

I grew up on the stories of Drew Kampion, specifically his Don Redondo series in the mid-‘70s, which were psychedelic and shamanistic and super trippy. At age 24, holding a BA in English from Cal State University Northridge, Drew became the editor of Surfer magazine. The year was 1968. The Shortboard Revolution was in full swing. Free love and weed smoking abounded, and Drew brought that spirit to the mag. He was a prolific writer, covering all facets of surfing. In ’72 he moved over to Surfing, where he documented the rise of professional surfing. He’s written over a half-dozen books. He wrote the VO script for the ‘70s classic film “Five Summer Stories.”

Today, Drew lives in Whidbey Island, where he’s the online editor of Drew’s List. He’s an avid cyclist. “Cycling is a lot like surfing,” he once told me. “The downhill is the ride, the uphill is the paddling back out.” My own cycling experience was enhanced tremendously from that day on.

We spoke via phone, he just off a bike ride on Whidbey Island, me quarantined and cabin-fevered-out in LA.

What’s the difference between the surf media today compared to your time at Surfer and Surfing?

Corporate ownership. Back then there was never any confusion about where the dollars came from, but there was a distinction between creative and financial. When I was at Surfer, when Hobie or anybody would come in or call, John Severson, the publisher, would go out the back stairs and just leave the building and get in his car and drive away so he didn’t have to talk to the advertising side of things. And then at Surfing it was kind of like that, too. The ads guys were pretty copacetic with the editorial guys. They didn’t get involved that much. But you could feel it as the ‘80s came—more advertising put pressure on the editorial.

What was your favorite part of the job?

When I started at Surfer, Severson had this other guy working there, Pat McNulty, who was moonlighting for the Saturday Evening Post. McNulty had much less interest in surfing, to my observation, and I was there for only about two weeks when John fired him. So I went from somebody John didn’t know to somebody John still didn’t know to his editor. And he just seemed to want to get out of the building a lot, but he gave me a really good education on how the magazine worked, how he had created this thing in the late ‘50s and the first couple years of the ‘60s, and then he got an art director in there, and then he got a couple of editors over the years that were competent editors. They knew how to run or work for a publication. And so he kind of learned from them.

So by the time I got there, John basically said, “This is how it works, and you’re in this position, so go for it.” And he just turned me loose. The magazine was very anti-drug. McNulty wrote editorials against the use of marijuana by surfers and things like that. And I was of a different mindset at the time. So one of the first opportunities I seized—because I could see John was curious because a couple of us were smoking at night at the magazine—was when he asked me to get him stoned. And I got him stoned. And then his wife, Louise, started to hate on me because I got him stoned. So John said, “How about we get Louise stoned?” And so we got Louise stoned. And Louise loved it. And after that the magazine became weed friendly. And weed friendly meant that we spent a lot of time during the day surfing Trestles and Cottons, and working a lot of times in the evenings. And I could do whatever I wanted.

So that’s when I got into writing a lot of fiction. I had sold a fiction story to Surfer that predated my editorship there. The story was about a guy that drops acid, and the reason they ran the story is the guy dies. Otherwise they never would have run it, I’m sure. It was nothing to do with me; it was just my timing. I was there at the right time.

Is there a piece you’re most proud of?

Some of the fiction I put in a book of short stories I did some years ago called “The Lost Coast.” I like that story: “The Lost Coast.” I always put attention on that one, which is interesting because I’d never been to The Lost Coast. It was probably 25 years or so ago that I wrote this thing. It’s about a guy that ventures into The Lost Coast, didn’t know where he was going, but he goes through a cattle gate and finds himself over the hill—sort of a perilous ride, kind of a mysterious thing in the outcome. But after I wrote that—it was in Surfing magazine, I think—I had several people who’d been to The Lost Coast compliment me on the accuracy down to the old house that was there that I didn’t even know existed. So that was a trippy one.

I remember your Lost Coast story. It really connected. Well, it’s great to catch up, Drew. Anything we didn’t talk about that you’d like to?

Yeah. I want to thank my ex-wife and early girlfriend who bought a Hobie surfboard one time, and I thought, “Shit, I’d better get a surfboard, too.” So I bought a surfboard so I could stay up with her, so to speak, in the world. And that’s why I got into surfing, and that’s why I’m talking to you today.

For more of Drew Kampion go HERE.